Network Management is a broad range of topics with a long history, stretching back to both the early days of telecommunications, as well as the early days of data networks. At one point, these were much more separate worlds, with different tools and techniques. Starting in the early 2000s, the two types of networks started to share best practices and tooling, where their different priorities did lead to some ‘net head’ versus ‘bell head’ disagreements. Today, there are still difference in goals, and the types of networks are more likely to be discussed in terms of enterprise versus carrier, on-prem versus cloud, but convergence has taken place in terms of adoption of data-centre concepts and common tooling for network management.

Functions

In general, when operating and managing a network, you want to be able to

- Do an initial deployment of the network and its supporting software (green field)

- Perform Moves, Adds, Changes,and Delete (MACD) to equipment in the network

- Perform regular maintenance, such as

- Software upgrades and security patches

- Replace failed equipment

- Monitor the network to ensure no failures, that Service Level Agreements (SLAs) are being met and to ensure that the network has sufficient capacity to meet upcoming needs

- Enable over the top customer services, as required.

- Troubleshoot issues discovered by tooling or reported by users.

- Manage trouble-tickets and customer orders.

- Activity audits, potentially required for legal reasons

- Billing, for used services

One traditional term used in network management, largely falling out of use, is FCAPS, which stands for Fault, Configuration, Accounting, and Security.

Exchanging information and Performing Tasks

There are many ways to talk to equipment being managed in the network, as well as the various bits of specialized software that help the solution scale

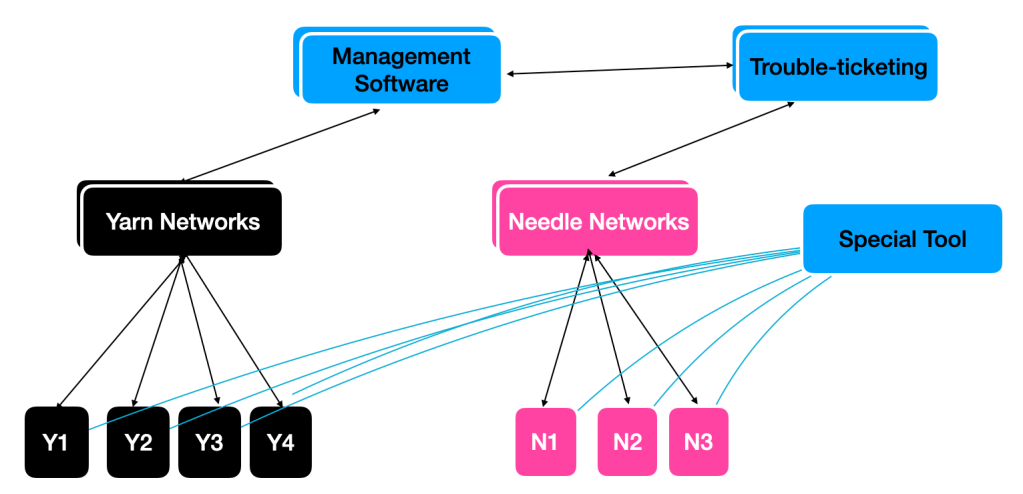

The following is an overly simplified architecture that demonstrates two different types of integration

We can see that we have a network that is made up of equipment from two different companies – Yarn Networks and Needle Networks. Both equipment vendors will expose management interface off of their equipment. This could be a simple Command Line Interface (CLI), SNMP, syslog or a REST API. In some cases all or part of interface may not be directly available to customers and be intended for either advanced users or software.

Since both Yarn Networks and Needle networks enable users to access their equipment directly, we have directly integrated both into a specialized tool. This could take the form of some simple scripting we have performed, or a an off the shelf tool we customized to be able to perform the specific functions we want, like IT automation or orchestration.

In our example, each of these network vendors provides their own management software that is familiar with best practice for managing their equipment and what they think are functions required. Historically, these were called Element Management Systems (EMS). They are two different pieces of software though, that each do things a bit differently, present slightly different information, and the network operator may not want to be logged into both systems all the time. Each of these then provide a North Bound Interface (NBI) that provides a useful subset of information and functions, that can be used either manually or integrated into other tooling.

We have included management software which talks to both the Yarn Networks and the Needle Networks software. It may replicate the information stored in there, like the list of equipment, and put it in a normalized form so we can perform common operations against all equipment. This common view could also include alarms, events, logs or performance/telemetry. This common set of data can provide both additional insights that the specialized software is incapable of and a single plane of glass to monitor the entire network. It may also perform network-wide configuration or orchestration.

This software may in turn be integrated into other systems, like trouble-ticketing, capacity planning or procurement.

You may notice that I have doubled up many of the boxes. This represents the Highly Available (HA) solution that is required in may cases.

Management Protocols and Command Line Interfaces (CLI)

Whether a formally defined protocol or a simple CLI, a management interface consists of three parts, which form the basis of the contract used between two parties to exchange information and perform operations

- Operation Syntax

- The protocol definition that format of requests and responses

- CLI Command Format

- SNMP verbs and format

- REST verbs and format

- The protocol definition that format of requests and responses

- Semantic Definition Languages or Format

- This defines the format and rules for defining content to be exchanged via the protocol we defined above

- Proprietary format for CLI

- Structure of Management Information (SMI) in SNMP

- JSON

- XML Schema

- RelaxNG

- JSON Schema

- This defines the format and rules for defining content to be exchanged via the protocol we defined above

- Actual Semantic Definitions

- Definitions related to the specific operation you wish to perform

- SNMP MIBs – Interfaces, Entity, Alarm, etc

- Redfish Schema – NetworkInterface, Chassis, Fan, etc

- Definitions related to the specific operation you wish to perform

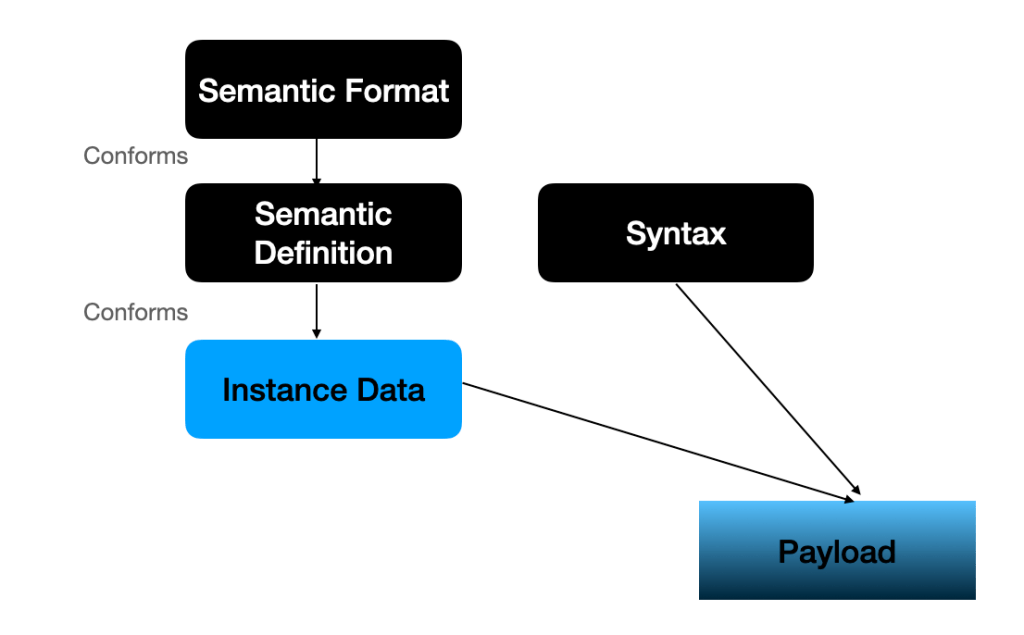

In the following picture, we see that we have instance data (a specific alarm, for example), which is compliant to a specific definition (SNMP Alarm MIB, for example), which is in turn compliant to a semantic format (SMI, for example). Together with the protocol syntax, we can create a payload that can be received and understood by the receiver.

Put another way, models (semantic definitions) are defined in modelling languages (semantic formats) while payload formats are defined separately, and include how to carry instances of models. Collectively this all defines the payload (actual bits on the wire), which two communicating parties can exchange without ambiguity, at least in theory.